Two Seconds / The Man with Two Faces

1934

Edward G. Robinson’s Films With Two Faces

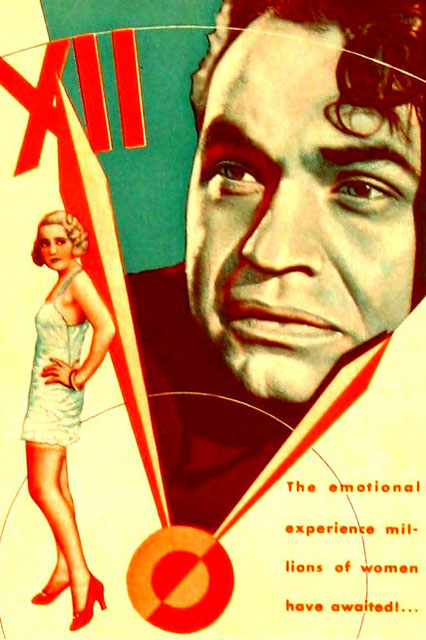

Mervyn LeRoy’s 1932 picture Two seconds opens with Robinson being led to the chair. Now already by this time audiences were getting used to seeing Robinson led to the chair, so many probably assumed they were in for another gangster picture. But the execution in this case is only a simple and neat framing device, and the moment the juice starts flowing LeRoy jumps to a flashback. Instead of a gangster film, however, audiences found themselves in what appeared to be a romantic comedy. John Allen (Robinson) and his roommate Bud (Preston Foster) are a couple of high steel workers. They joke around, talk about money and girls, but ultimately Allen is the more philosophical of the two, and bemoans his lack of education. After some hijinx involving a bookie and a double date, Allen finds himself at a dime-a-dance joint, where he meets Shirley ( Vivienne Osborne), a nice girl with dreams of going to business school. After Robinson punches a patron who was trying to get fresh (Robinson’s third dancefloor dustup by my count) he and Shirley become an item. Everything is light and breezy and charming and funny, even if bud is convinced Shirley is nothing but a gold-digging whore.

In a scene that is both comic and frightening, Shirley reveals herself to be just that by tricking Allen into marrying her while he’s too drunk to stand. The friction between Allen and Bud increases, culminating in a confrontation some sixty stories up at a construction site. Bud comes right out and tells Allen his wife’s a prostitute. Allen swings at Bud, who plummets to his death.

At that instant what had been a light romantic comedy takes a very sharp and very dark left turn, as Allen falls into an immobilizing depression and Shirley becomes a cruel shrieking harridan. Unable to leave the apartment to find work, Allen is forced to accept his wife’s earning’s as a hooker to pay the rent and grocery bills. By the time an unexpected winfall comes his way Allen has gone completely mad, and sets out to repay all his debts. The last twenty minutes of the film are a tour-de-force for Robinson. In a courtroom scene unlike any other, Robinson raves alone on a dark stage, trying to explain what he means when he tells the judge he’s being killed at the wrong time. It’s very stagey of course (the film was based on a popular stage play), but on film it comes off as dreamlike—or more accurately nightmarish—with Robinson’s carachter a thousand miles away from the man we met in those lighthearted opening scenes. It would only be the first of several Edward G. Robinson films that would throw audiences a curveball—being, by all appearances, one kind of film in the opening minutes (even the opening half) then veering sharply in another direction with an accompanying shift in mood and tone and genre. It was almost as if Robinson was delivering two films in one; in any case he certainly had to deliver at least two performances in one—and in the case of Two SEconds, it was more like four: the wisecracking, philosophical construction worker, the giddy shy kid on a first date, the helpless depressive, and the raving but still logical madman. (It’s pretty amazing, to be honest).

He pulled that same trick in 1934 in Dark Hazard, which is a borderline case in this particular category. Based on a novel by the great W. R. Burnett and directed by Alfred E. Green (whose later career would be marked by a string of popular biopics), the film is a shaggy dog story, hardly the powerhouse of Two Seconds, but still interesting, especially in terms of Robinson’s performance.

Here he plays Jim “Buck” Turner, a professional gambler who hits a streak of bad luck, moves into a family-run boarding house, and falls for the daughter ( Genevieve Tobin). After promising he’ll go straight, they marry, move to Chicago, and he takes a job as a night desk clerk at a hotel. A big-time mobster (Sidney Toler) ... gets Turner fired, then immediately hires him and sends him to California to keep an eye on a dog track to make sure it’s being run on the up-and-up.

Well, it’s not long before Turner starts gambling again and runs into an old flame (Glenda Farrell). Across the rest of the film, his marriage deteriorates, rekindles, and deteriorates again, echoing the rise and fall and rise and fall of his gambling fortunes. By the end of Dark Hazard we have returned once again to where we began. No one has changed, no one has learned anything, and we’re given the clear idea that the cycle will simply roll on as it always has.

It’s a schizophrenic film not so much in terms of the changing styles or the detouring storyline, but rather in terms of Robinson’s constantly shifting performance. At any given moment throughout the film, he’s playing one of four very different characters, who have little or nothing to do with one another, and switch places almost from scene to scene. One moment he’s the cool gambler, then a tough guy, then a henpecked husband, then, for some reason, Timmy from the old Lassie series (later in the film he becomes smitten with a greyhound—Dark Hazard—and reverts to childhood whenever he’s in the dog’s presence). Pull any single scene out and watch it independently from the rest of the film, and you’d come away with a very different idea concerning what kind of picture it really is—sort of like the blind men and the elephant. It’s a little unnerving but oddly realistic. Like most of us his life and the film march on through a series of random coincidences and well established patterns, and he approaches each with the personality that fits best. In cinematic terms it feels quite strange. In simple human terms not so much.

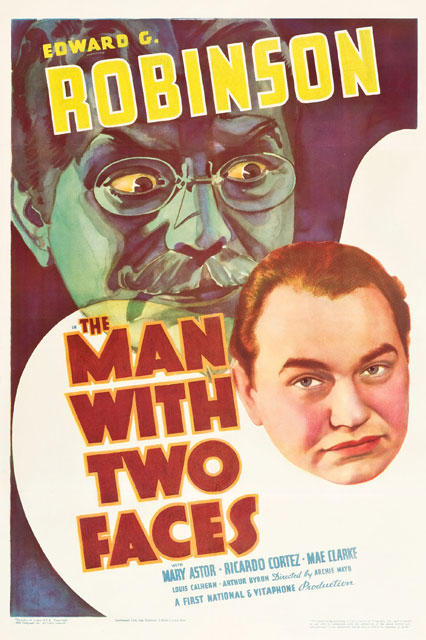

By all appearances, that same year’s Man With Two Faces is going to be little more than a breezy bit of highbrow fluff.

The Archie Mayo-directed film opens as a backstage comedy, with a family-based theatrical troupe celebrating a new play and the comeback of Jessica Wells (Mary Astor), a once-famous actress who had a breakdown following the shooting death of her evil and controlling husband Stanley Vance. Robinson plays Damon, Jessica’s brother and co-star in the new play, a wisecracking cynic and drunk. The jokes and insults fly fast and furious as the members of the extended family are introduced, and the lighthearted backslapping and backbiting begin.

Well, all the jokes seem to vanish quickly with the unexpected arrival of Jessica’s late husband, who has some kind of hypnotic control over her. Everyone else hates him and wants him dead—and to be fair, he is kind of a dick. Vance interferes with his wife’s career and the financing of the play, and even destroys her acting ability when he’s around. There is a big surprise at the climax in which Robinson’s carachter plays a major role, then an unstated implication at the end of the film that slipped right by the Hays Code. Still although the shift in tone takes place within the first fifteen minutes, it remains a bit jarring. Ass a whole, however, the film is probably the least interesting of the lot despite Robinson’s performance.

Seven years later in 1941, Raoul Walsh directed Manpower, a film that shares quite a bit in common with the earlier Two Seconds, but pushes the idea of “two films in one” to even greater and more perplexing extremes.

Notable for having some of the most dramatic and savage thunderstorm scenes ever caught on film, the picture begins like a screwball workplace comedy with the one-liners zinging this way and that. Once again (as in Two Seconds) Robinson is a blue collar worker, Hank—in this case a lineman for the electric company. His buddy and co-worker this time is Johnny (George Raft) A Again we get to see Robinson dance, and again he gets into a fistfight on the dance-floor, and again he has trouble with the girls, though he’ll never admit it.

It’s all wackiness and lightning-paced hijinx until the daughter of the line crew’s foreman (Marlene Dietrich) gets out of prison. Again Hank is smitten and his buddy is convinced she’s bad news. The film takes a sudden turn toward the dour as Dietrich’s intentions become clear. A

scene between Robinson and Dietrich in a clip joint even mirrors a scene from Two Seconds, as does the scene in which Raft tells Dietrich to stay away from his friend.

The strange thing about the film is that unlike Two Seconds, in Manpower Walsh keeps bouncing back and forth between the wacky comedy and the grim drama with the two rarely if ever touching one another, and this continues throughout the film. It really is two films taking place at the same time. The closest to a turning point in the film might lay in the fact that Dietrich wears black on her wedding day.

Somehow, though, Walsh makes it ultimately work, strange as the whole thing feels. Part of the ttrick may be that Walsh plays both genres equally and naturally, without giving more credit or legitimacy to one or the other. Robinson doesn’t have a big tour-de-force scene at the end as he did in Two Seconds, but Manpower remains just as strange a film, and just as strong.

Considering all these films as a group, you have to wonder what happened along the way. Was the screenwriter a manic-depressive? Did the director change his mind about what kind of film he was making without bothering to do anything about the scenes already in the can? Was it a decision from higher up after someone saw the rushes? Or were these films merely an attempt to reflect what real life is like sometimes? And more curiously, how is it that Robinson ended up in so many of these schizophrenic pictures?

Copyright 2015